How to make TypeScript infer types in switch statements without casting

ArticlePublished on February 1, 2022 by ilDon

As a developer with very poor memory, I really like coding in typed languages. They allow me to forget my data types, and be sure to pass the right props around my code. If you are unfamiliar with typed languages, I suggest you read this book for a general overview, or this article for a more specific hands-on guide for TypeScript.

One annoying thing about developing in TypeScript is that it is not obvious how to infer types in switch statements. This is because the compiler doesn't know what type we are passing to the switch statement.

I will explain my solution to this problem by example, posting here the relevant part of the code needed to achieve the desired result. I have also set up a live (working) example of the code in this StackBiz project. Because I first developed this while working on a Redux reducer, I will provide an example that imitates what I would do in a Redux reducer. Since it is a simple use-case, it can easily be applied to any other scenario in which you need to infer types in switch statements.

I will focus on the how-to part, not the why-it-works part. I came across this solution after I had already written a switch statement in TypeScript. I was not trying to make TypeScript infer types, I was only being as precise as possible in my typing. Turns out, the compiler picked up more than I expected.

In short:

Defining the data types

This is by far the most important part of this solution. I will explain the data types that I will be using in this example.

Let's assume that we have an Object of type Element in our app:

interface Element {

id: string;

title: string;

description: string;

}

In our reducer we want to be able to set , update, clone, and, finally, clear the element.

We use a enum to define the action we want to perform:

enum ACTIONS {

setElement = 1,

updateElement = 2,

clearElement = 3,

clone = 4,

}

These actions will be the case to evaluate in our switch statement. Using a enum to map the cases we need to evaluate is crucial to make this whole solution work.

Now, to make things a little tricker, let's assume that we do not always want to pass a payload to our reducer. For example, we might want to clear the element, but we don't want to pass a payload for that.

Let's first define a union type of the enum values that do not require a payload:

type ActionsWithoutPayload = ACTIONS.clearElement | ACTIONS.clone;

Now we can divide our ACTIONS in two different interfaces, one for actions that require a payload, and one for actions that do not:

interface ActionWithoutPayload {

type: ActionsWithoutPayload;

}

interface ActionWithPayload<T extends ACTIONS> {

type: T;

payload: ActionsPayloads[T];

}

Note that ActionWithPayload is a generic interface that requires one type parameter, which is the enum we defined above.

ActionWithPayload has also a prop payload, which is the payload of the action. In this case we refer to the interface ActionsPayloads, which we can define as follows:

interface ActionsPayloads {

[ACTIONS.setElement]: Element;

[ACTIONS.updateElement]: Pick<Element, 'title' | 'description'>;

[ACTIONS.clearElement]: never;

[ACTIONS.clone]: never;

}

Note that we include all enums in ActionsPayloads, even those that do not have a payload. That is because, otherwise, we could not map ActionsPayload with the enum ACTIONS as we do in the ActionWithPayload interface (payload: ActionsPayloads[T]).

Finally, we can define the Action interface as follows:

type Action<T extends ACTIONS> = T extends ActionsWithoutPayload

? ActionWithoutPayload

: ActionWithPayload<T>;

Using the type Action in a switch statement

Having defined our types, we can now use them in our switch statement.

Let's first define the state we want to use in our switch statement. This is not strictly necessary for our example, but it makes it easier to understand what is happening:

interface IFormState {

element: Element | null;

}

Now let's put it all together:

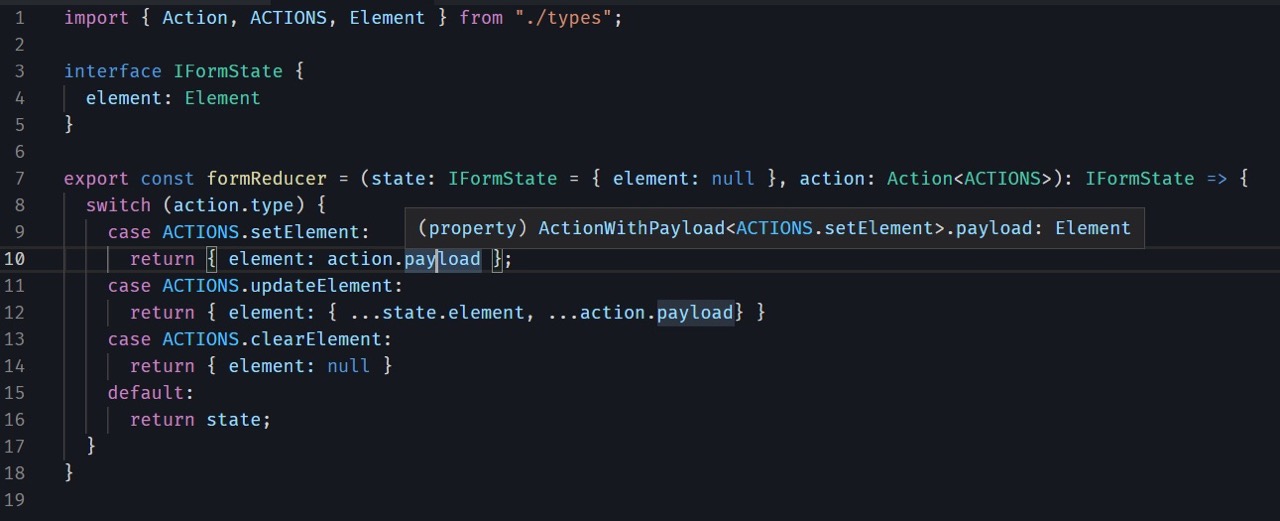

export const formReducer = (state: IFormState = { element: null }, action: Action<ACTIONS>): IFormState => {

switch (action.type) {

case ACTIONS.setElement:

return { element: action.payload }; // TypeScript infers that `action.payload` is of type `Element`

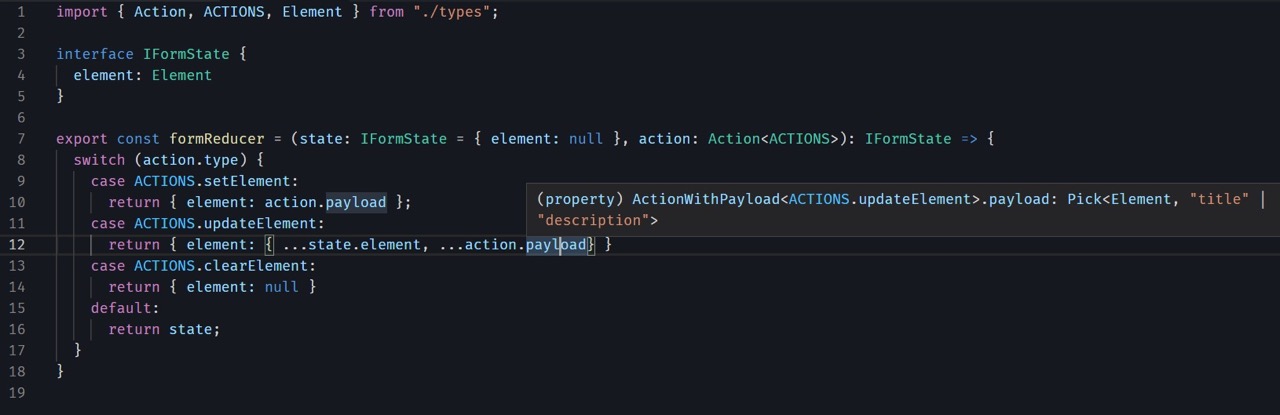

case ACTIONS.updateElement:

return { element: { ...state.element, ...action.payload } }; // TypeScript infers that `action.payload` is of type `Pick<Element, 'title' | 'description'>`

case ACTIONS.clone:

return { element: { ...state.element } };

case ACTIONS.clearElement:

console.log(action); // Typescript knows that `action` is of type `ActionWithoutPayload`

return { element: null };

default:

return state;

}

};

And that's pretty much it.

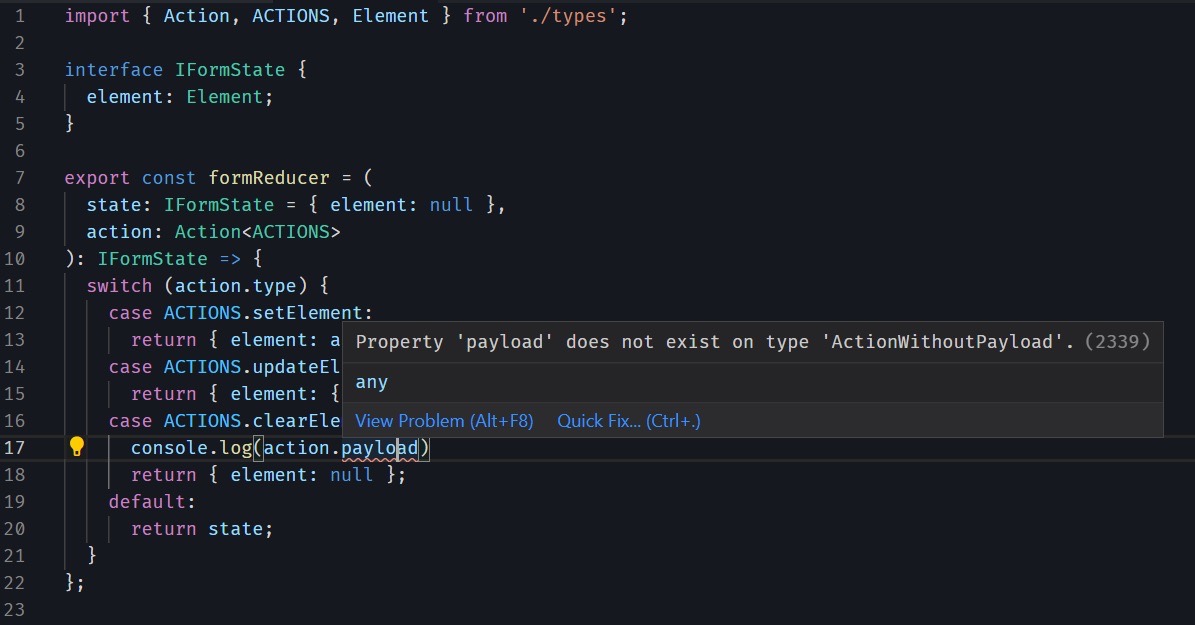

Some screenshots of the code in action:

Setting the element:

Updating the element:

Clearing the element:

As mentioned above, you can also check out the code in action in the SwitchWithTypes StackBiz project, with live type checking.

Conclusion

Using a switch statement with enums and interfaces as shown above is a great way to make your code more readable and maintainable.

We could of course simply cast the type. However, that is more manual work for us, and it is error-prone. Having TypeScript automatically infer the types in our switch statements is a much better way to ensure type consistency.

If you want to dig more into live examples, you can always check the Anita code repository, and in particular the folder with the Redux related files, or you can check out the TypeScript documentation.